Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime. – Mark Twain

Twenty-five years ago, today, I did something extraordinary. It began with my first international flight. In truth, it was the first time I was ever on a plane. I was part of a group that took off from Baltimore-Washington International and landed in Moscow, Russia. To make the trip, I had to get my first passport.

The Soviet Union split up in December 1991, slightly more than a year before. President Boris Yeltsin led the Commonwealth of Independent States, the loose organization that followed. President George W. Bush was in Russia for his final state visit before leaving office, having lost the election to Bill Clinton. We weren’t affiliated with Bush at all, although many people thought we were because of the doors that got opened for us.

The Soviet Union split up in December 1991, slightly more than a year before. President Boris Yeltsin led the Commonwealth of Independent States, the loose organization that followed. President George W. Bush was in Russia for his final state visit before leaving office, having lost the election to Bill Clinton. We weren’t affiliated with Bush at all, although many people thought we were because of the doors that got opened for us.

I can still point to that trip as one of the single-most important things I’ve ever done in my career. It set things in motion that I wouldn’t even come to realize for many years. I met people who would change my life and those experiences opened doors for many other aspects of my career.

It all began with an invitation from my friend and mentor Dr. Virginia Simmons who invited me along with a group of educators traveling to what was then called Kaliningrad, a suburb of Moscow. Kaliningrad was renamed Korolev, in honor of Sergey Korolev. He was the father of the Russian space program and the city was the home to their Russian Space Flight Control Center – their Houston Control.

I will never forget walking through the dim halls of Sheremetyevo International Airport to be confronted by a Russian border guard for the first time. He didn’t speak any English and I didn’t speak any Russian. I simply handed him my brand-new passport and hoped I wouldn’t be whisked off to some back room for interrogation.

That evening, the group I was traveling with was hosted at a group dinner. There was a buffet of light meats, bread and vegetables. My friends and I all thought, “We are hungry and this is perfect. We don’t want to insult our guests by not eating.” So, of course, we all went back to the buffet a couple times. And then they brought out the next course. And the next one. It ended up being a long dinner with multiple courses and lots of toasting and drinking. We were eight time zones away, jet lagged and miserable. But we also began friendships that have lasted until today.

That evening, the group I was traveling with was hosted at a group dinner. There was a buffet of light meats, bread and vegetables. My friends and I all thought, “We are hungry and this is perfect. We don’t want to insult our guests by not eating.” So, of course, we all went back to the buffet a couple times. And then they brought out the next course. And the next one. It ended up being a long dinner with multiple courses and lots of toasting and drinking. We were eight time zones away, jet lagged and miserable. But we also began friendships that have lasted until today.

Amidst the tours and meetings, one evening we were invited to have dinner in the homes of our Russian hosts. The mother handled public relations and communications for Kaliningrad so she got to deal with the reporter on the trip. She spoke pretty good English. I will never forget accidentally dropping a few pieces of red caviar from my bread, directly into a shot glass of vodka I was about to drink. The father, who didn’t speak any English, smiled at me and dropped a couple pieces of caviar into his own drink. We toasted and drained our glasses of vodka and caviar together.

Amidst the tours and meetings, one evening we were invited to have dinner in the homes of our Russian hosts. The mother handled public relations and communications for Kaliningrad so she got to deal with the reporter on the trip. She spoke pretty good English. I will never forget accidentally dropping a few pieces of red caviar from my bread, directly into a shot glass of vodka I was about to drink. The father, who didn’t speak any English, smiled at me and dropped a couple pieces of caviar into his own drink. We toasted and drained our glasses of vodka and caviar together.

Nearly every evening after guided tours around Moscow and the Russian space program, we reconvened back in our hotel in a common room with our tour guides and interpreters and just talked. I have fond memories of Nadia, Natasha, Ludmilla and others, along with Anatoly, Vladimir and Alexey who was the deputy mayor of Kaliningrad and our primary host for the trip. The vodka flowed, of course, and we laughed and joked and got to know each other. One thing that struck me from those conversations was the declaration that the Russians felt their government had lied to them for many years. “We were told for 70 years that we had the best of everything. Now we find out we were lied to.”

Nearly every evening after guided tours around Moscow and the Russian space program, we reconvened back in our hotel in a common room with our tour guides and interpreters and just talked. I have fond memories of Nadia, Natasha, Ludmilla and others, along with Anatoly, Vladimir and Alexey who was the deputy mayor of Kaliningrad and our primary host for the trip. The vodka flowed, of course, and we laughed and joked and got to know each other. One thing that struck me from those conversations was the declaration that the Russians felt their government had lied to them for many years. “We were told for 70 years that we had the best of everything. Now we find out we were lied to.”

Another thing they told us was that they felt very disconnected to their government. There is a big difference between the actions of the Russian government and the attitudes of the Russian people. I believe that still holds true.

One focus of the trip was education. The group were mostly educators, invited to Kaliningrad/Korolev to help the city rebuild and restructure its educational system. After the fall of communism, they discovered their text books and educational methods were hopelessly out of date. We visited numerous schools and were impressed in some ways, and disheartened in others.

One focus of the trip was education. The group were mostly educators, invited to Kaliningrad/Korolev to help the city rebuild and restructure its educational system. After the fall of communism, they discovered their text books and educational methods were hopelessly out of date. We visited numerous schools and were impressed in some ways, and disheartened in others.

I remember, about a year and a half after that first trip, having a long, vodka-fueled argument with a Russian friend about communism and its relative merits. I tried to say that what the Russians had experienced wasn’t communism at all, but Alexey wasn’t hearing any of it. Ultimately, we ended the discussion and by the next morning, he had put it aside. We remained friends—although I understood he was angry with me for a while. I realize now just how naïve my assertions were. He had lived through the fear and deprivation. My textbook answers and arguments had nothing to do with life on the ground.

Coming home, even understanding the context of the time, I was stunned to hear people I knew make comments like “They are all just commies, we should kill them all.” I was traveling as a journalist, but ended up being interviewed myself several times. I often quoted a line from the Sting song “Russians” from 1985.

Coming home, even understanding the context of the time, I was stunned to hear people I knew make comments like “They are all just commies, we should kill them all.” I was traveling as a journalist, but ended up being interviewed myself several times. I often quoted a line from the Sting song “Russians” from 1985.

“There is no monopoly on common sense

On either side of the political fence.

We share the same biology, regardless of ideology.

Believe me when I say to you,

I hope the Russians love their children, too”

I usually followed that up with the belief, that Sting implied, that they did. These were people I had laughed with and joked with. They were friends. I couldn’t believe people would wish death on my friends.

That first trip served as the motivation for the creation of the nonprofit Russia and West Virginia Foundation that supported hundreds of student, teacher and cultural exchanges.

In 2008, 15 years after my first trip to Russia, I went back and photographed many of the people and places I saw on that first trip, and subsequent trips I made in the 90s. In 2010, I took those photographs to Moscow and exhibited them in Moscow. The reaction was interesting to watch. It was fun to see the people looking at side-by-side photos of themselves. But it was just as interesting to see spectators who had no connection to the photos, comparing their memories to the ones captured in the photos. They were looking at clothes and hairstyles and laughing. The images showed life 15 or so years before, but in a lot of ways it reflected another world.

In 2008, 15 years after my first trip to Russia, I went back and photographed many of the people and places I saw on that first trip, and subsequent trips I made in the 90s. In 2010, I took those photographs to Moscow and exhibited them in Moscow. The reaction was interesting to watch. It was fun to see the people looking at side-by-side photos of themselves. But it was just as interesting to see spectators who had no connection to the photos, comparing their memories to the ones captured in the photos. They were looking at clothes and hairstyles and laughing. The images showed life 15 or so years before, but in a lot of ways it reflected another world.

All together, I made seven trips to Russia, encompassing more than six months living in the country. Since then, I have made dozens of international trips to more than 25 other countries. It all started with that first trip and that first passport. I’ve had one every since and even had to have extra pages added to my last one.

All together, I made seven trips to Russia, encompassing more than six months living in the country. Since then, I have made dozens of international trips to more than 25 other countries. It all started with that first trip and that first passport. I’ve had one every since and even had to have extra pages added to my last one.

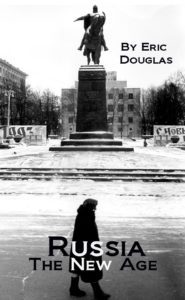

Five years ago, for the 20th anniversary of that first trip, I published an e-book called Russia: The New Age with news stories I wrote and essays from the 90s along with blog posts and essays from 2008 and 2010 when I returned to see how things had changed. It also includes most of the photos from the 2010 photo exhibit that was also shown in Bordeaux, France, and in Charleston, West Virginia and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. You can check it out here.

Five years ago, for the 20th anniversary of that first trip, I published an e-book called Russia: The New Age with news stories I wrote and essays from the 90s along with blog posts and essays from 2008 and 2010 when I returned to see how things had changed. It also includes most of the photos from the 2010 photo exhibit that was also shown in Bordeaux, France, and in Charleston, West Virginia and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. You can check it out here.

The last 25 years have brought some challenges, but even more amazing opportunities. I can’t wait to see what happens in the next 25.