One of the story lines in my new novel Return to Cayman is a cruise ship dropping anchor on a living reef. This scenario is loosely based on a cruise ship grounding off of Don Foster’s reef last August when the Carnival Magic dropped its anchor and hundreds of feet of anchor chain destroying an estimated 16,000 square feet of reef. Since the incident, volunteers have spent thousands of hours cleaning up the site and working to keep the damage from getting worse.

One of the story lines in my new novel Return to Cayman is a cruise ship dropping anchor on a living reef. This scenario is loosely based on a cruise ship grounding off of Don Foster’s reef last August when the Carnival Magic dropped its anchor and hundreds of feet of anchor chain destroying an estimated 16,000 square feet of reef. Since the incident, volunteers have spent thousands of hours cleaning up the site and working to keep the damage from getting worse.

At the book signing/release party for the novel at Sunset House, Joey Avary, a reporter for the Cayman 27 news channel, stopped by to do a story. In talking to him, I found out that he was very involved in the Cayman Magic Reef Restoration project. I mentioned I would like to see the site and he said he was free on Friday.

When he briefed the dive, Avary said we would do a tour, but he also brought along a couple toothbrushes so we could clean some algae off the coral. If you’ve never tried to hover in one place, in acurrent, and scrub algae from monofilament fishing line with a toothbrush while not breaking the fragile structure the salvaged pieces were hanging from, you haven’t lived. I was sure I was going to set the project backward. Avary made it look easy, but I felt like a politician during a photo op at a soup kitchen. (At least a politician that knows better than to believe his own press).

When he briefed the dive, Avary said we would do a tour, but he also brought along a couple toothbrushes so we could clean some algae off the coral. If you’ve never tried to hover in one place, in acurrent, and scrub algae from monofilament fishing line with a toothbrush while not breaking the fragile structure the salvaged pieces were hanging from, you haven’t lived. I was sure I was going to set the project backward. Avary made it look easy, but I felt like a politician during a photo op at a soup kitchen. (At least a politician that knows better than to believe his own press).

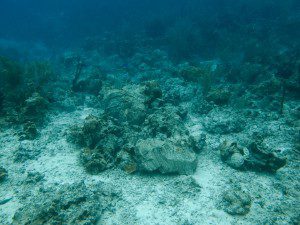

When you approach the site, everything looks normal, right up until it doesn’t. Coral is growing and fish are swimming. We saw a couple sea turtles nearby. And then you get the impact spot. T here’s just nothing there. And it’s not just one place. It goes on for hundreds of yards. The anchor and chain turned the reef into rubble in an instant. It looks like a massive scar across the sea floor. And that’s after months of work.

here’s just nothing there. And it’s not just one place. It goes on for hundreds of yards. The anchor and chain turned the reef into rubble in an instant. It looks like a massive scar across the sea floor. And that’s after months of work.

Lois Hatcher is the underwater project director. She worked on the Masdam grounding in Cayman in 1996. In 2011 she spent a year in the Florida Keys studying coral restoration and ecology along with an internship with Ken Nedimeyer at the Coral Restoration Foundation. She returned to Cayman two years ago with the sole intention of getting a coral nursery started.

“The biggest challenges is getting past the nay-sayers and politicians. We have been held back by this and all we really want to do is stabilize the reef, save what coral we can and go back to enjoying the coral reef not putting it back together. The time line keeps being adjusted but hopefully in the next couple of weeks we will start using concrete to secure the bigger pieces, fill in the gaps with smaller pieces and epoxy and finish off the rubble removal in a couple of areas. I am hoping that this is only going to take three to four months of consistent work. We won’t know though until we actually get started and get the rhythm going,” she explained.

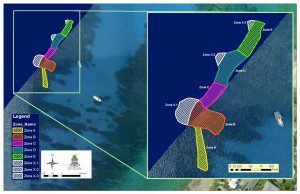

During the tour, Avary showed me a section that is roped off with a sign that reads “Keep Out.” When the anchor chain dragged on the relatively shallow reef, it piled up debris at the top of a channel. The rubble pile is so unstable, if disturbed, it could cause an avalanche down the wall, tearing up even more reef. “It is deeper than recreational diving limits, but just because we can’t see it that doesn’t mean it’s not important,” Avary said.

During the tour, Avary showed me a section that is roped off with a sign that reads “Keep Out.” When the anchor chain dragged on the relatively shallow reef, it piled up debris at the top of a channel. The rubble pile is so unstable, if disturbed, it could cause an avalanche down the wall, tearing up even more reef. “It is deeper than recreational diving limits, but just because we can’t see it that doesn’t mean it’s not important,” Avary said.

Volunteer divers have been sorting through the rubble, finding viable pieces of coral, and separating it by type. They’ve cleaned away silt and debris to save what they could.

Volunteer divers have been sorting through the rubble, finding viable pieces of coral, and separating it by type. They’ve cleaned away silt and debris to save what they could.

“The crates are used as a temporary holding area for the pieces that need to be reattached. It was made from materials that we had on hand and used to avoid “losing” loose corals in the reef or placing them in the sand. The crates keep the species separate, allow for water flow and keep the pieces off the sand so they don’t choke from sedimentation,” Hatcher explained. “The prognosis also changes with time. Obviously the longer that coral is in an unstable environment the less chance it has of recovery. The pieces that we have outplanted are all doing well but the installation of a cruise ship dock could change all that.”

Even while doing all of this work, the volunteers have to constantly watch depth and time limits and coordinate the tasks using hand signals and writing slates. To get to work, the volunteer divers make a surface swim the couple hundred yards out until they are on top of the site to save their air for more work time underwater. This makes for a long tiring swim before they even get to work. And then, of course, they have to swim back to the shore afterward. The project should have its own boat soon. That should make the process easier and more efficient, although a boat takes fuel and maintenance, all of which cost money. (Update: the group has taken possession of the boat, named Honey Badger and it is already paying tremendous dividends on their work productivity. By removing the long surface swim, they are able to do two and three dives in a day and have the tools they need right on site.)

During the interview, Avary asked why I was interested and why I would be willing to donate a portion of the royalties from Return to Cayman to the reef recovery effort. I told him that while I don’t live there, and had never actually visited that reef before the accident, it was still important to me. I think of the ocean as mine. For me, it seemed like as simple thing to do, especially compared to the work the volunteers are doing. Through July 31, I will donate a portion of royalties from the book Return to Cayman to the reef recovery effort. The book is available in softcover and on Kindle.

During the interview, Avary asked why I was interested and why I would be willing to donate a portion of the royalties from Return to Cayman to the reef recovery effort. I told him that while I don’t live there, and had never actually visited that reef before the accident, it was still important to me. I think of the ocean as mine. For me, it seemed like as simple thing to do, especially compared to the work the volunteers are doing. Through July 31, I will donate a portion of royalties from the book Return to Cayman to the reef recovery effort. The book is available in softcover and on Kindle.

One of the great things about writing fiction is that while you are entertaining, you can also educate and inform. In fact, one of the best ways to educate is by making it entertaining. My goal was to do both with Return to Cayman.

If you are interested in making a donation to keep this project going, the Cayman National Trust has a tab under “Donate” for the project. Even volunteer projects take money.

Side note: Grand Cayman is now weighing the installation of a cruise ship dock that would possibly eliminate incidents like this. However, to construct the dock, they would have to destroy an estimated 15 acres of living coral reef, including Devil’s Grotto, and damage another 15 to 20 acres. .